Today, a colleague handed me a .pyd file and asked me to run some data analysis. I was completely stumped…

I wonder how many of our readers know how to run .pyd code files? If you’re also feeling confused, please continue reading!

Today, let’s popularize the various Python code file extensions and provide some essential knowledge for Python developers.

.py

The most common Python code file extension, officially referred to as Python source code files.

No need for extensive explanation here~

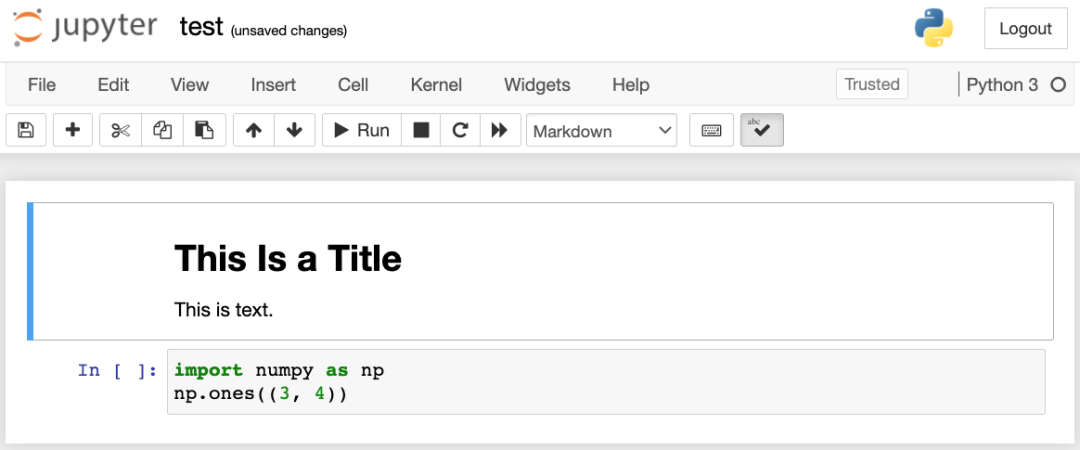

.ipynb

This is quite common too. .ipynb is the extension for Jupyter Notebook files, standing for “IPython Notebook.”

Students who have studied data analysis, machine learning, or deep learning must be familiar with this!

.pyi

.pyi files are type hint files in Python, used to provide static type information for code.

They’re generally used to help developers with type checking and static analysis.

Example code:

python

# hello.pyi

def hello(name: str) -> None:

print(f"hello {name}")

The naming convention for .pyi files is typically the same as the corresponding .py files so they can be automatically associated together.

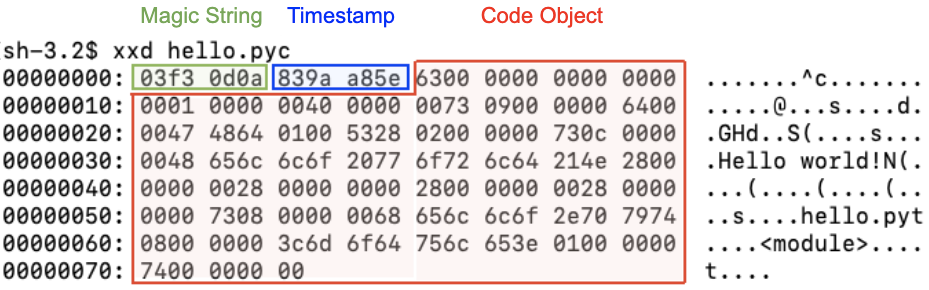

.pyc

.pyc is the extension for Python bytecode files, used to store the intermediate representation of compiled Python source code. Since it’s a binary file, we cannot normally read the code inside.

.pyc files contain compiled bytecode, which can be loaded and executed faster by the Python interpreter since it doesn’t need to compile the source code again.

.pyd

.pyd is the extension for Python extension modules, used to represent binary Python extension module files written in C or C++.

.pyd files are compiled binary files that contain the compiled extension module code and information needed for interaction with the Python interpreter.

Additionally, .pyd files are imported and used in Python via import statements, just like regular Python modules.

Since C or C++ typically executes faster than pure Python code, you can use extension modules to optimize the performance of Python code, especially for computation-intensive tasks.

.pyw

.pyw is the extension for Python windowed script files.

It represents a special type of Python script file used to create windowed applications without a command-line interface (i.e., console window).

Normally, running Python scripts opens a command-line window displaying script output and accepting user input. However, for certain applications, like graphical user interface (GUI) applications, a command-line interface isn’t needed – instead, you want to display an interactive interface in a window. This is where .pyw files come in.

Example code:

python

# click_button.pyw

import tkinter as tk

def button_click():

label.config(text="Button Clicked!")

window = tk.Tk()

button = tk.Button(window, text="Click Me", command=button_click)

button.pack()

label = tk.Label(window, text="Hello, World!")

label.pack()

window.mainloop()

.pyx

.pyx is the extension for Cython source code files.

Cython is a compiled, statically typed extension language that allows using C language syntax and features in Python code to improve performance and interact with C libraries.

I compared the execution speed of Cython vs regular Python:

fb.pyx (needs to be compiled using the cythonize command)

python

import fb

import timeit

def fibonacci(n):

if n <= 0:

raise ValueError("n must be a positive integer")

if n == 1:

return 0

elif n == 2:

return 1

else:

a, b = 0, 1

for _ in range(3, n + 1):

a, b = b, a + b

return b

# Pure Python version

python_time = timeit.timeit("fibonacci(300)", setup="from __main__ import fibonacci", number=1000000)

# Cython version

cython_time = timeit.timeit("fb.fibonacci(300)", setup="import fb", number=1000000)

print("Pure Python version execution time:", python_time)

print("Cython version execution time:", cython_time)

run.py

python

import fb

import timeit

def fibonacci(n):

if n <= 0:

raise ValueError("n must be a positive integer")

if n == 1:

return 0

elif n == 2:

return 1

else:

a, b = 0, 1

for _ in range(3, n + 1):

a, b = b, a + b

return b

# Pure Python version

python_time = timeit.timeit("fibonacci(300)", setup="from __main__ import fibonacci", number=1000000)

# Cython version

cython_time = timeit.timeit("fb.fibonacci(300)", setup="import fb", number=1000000)

print("Pure Python version execution time:", python_time)

print("Cython version execution time:", cython_time)

Results obtained:

text

Pure Python version execution time: 12.391942400000516 Cython version execution time: 6.574918199999956

In this computation-intensive task scenario, Cython was nearly twice as efficient as regular Python.