After gaining a basic understanding of the previous content, we will now explore the Pandas section with greater freedom and ease to implement more functionalities.

Pandas is a Python software library built on top of NumPy for data analysis and manipulation. It provides data structures and operations for handling numerical tables and time series, along with some visualization capabilities.

About Pandas

The name “Pandas” itself is quite peculiar. Why would a library for handling tables be named after a “panda”? Is it a tribute to a legendary founder’s hobby?

Actually, since Pandas was originally designed for data analysis in econometrics, its name is derived from the field’s technical term “Panel Data.”

Additionally, there’s a plausible-sounding but non-factual explanation: Pandas is an acronym for “Python Data Analysis.”

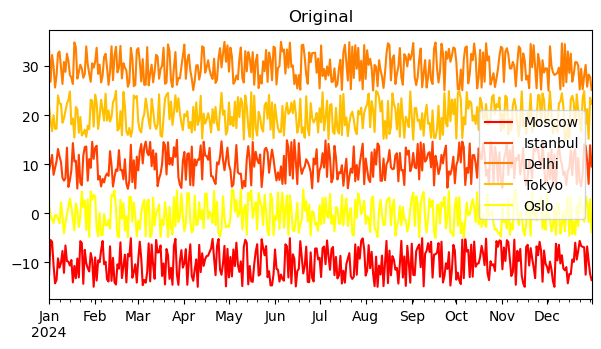

In the field of geoscience, our practical work involves processing various types of data. Ultimately, we need to summarize them into specific characteristics to describe phenomena or explain principles.

For example, the mean, sum, etc., of a certain variable; the relationship between A and B; trends over a specific period.

Pandas can help us process this data quickly and efficiently, making it easier to extract valuable information.

Today’s story begins with Pandas’ basic data structures and indexing!

Pandas Data Structures

Pandas has three basic data structures: Series, DataFrame, and MultiIndex.

Simply put, a Series can be seen as a table with only one column; a DataFrame is similar to the commonly used Excel spreadsheet, a more flexible two-dimensional table; MultiIndex is a tabular structure with multi-level indexing.

Due to the complexity of MultiIndex, we won’t delve into it this session. Series and DataFrame can meet most of our application scenarios.

Series

As mentioned earlier, a Series can be viewed as a table with only one column. Unlike a one-dimensional array, a Series has row names and a column name.

Both Series and DataFrame can be indexed using labels (row/column names) or positional indexing (the M-th row, N-th column), allowing for more convenient data indexing and manipulation.

We can create a Series in multiple ways. Let’s look at some examples.

python

import pandas as pd # Create a Series using a list temperature = [10, 15, 20, 25, 30] ser = pd.Series(temperature, index=["2021-01-01", "2021-01-02", "2021-01-03", "2021-01-04", "2021-01-05"], name="Temperature") print(ser, '\n') print(ser.index) # Row index print(ser.values) # Values print(ser.name) # Name print(ser.dtype) # Data type print(ser.shape) # Shape print(ser.ndim) # Dimensions print(ser.size) # Size # Output: # 2021-01-01 10 # 2021-01-02 15 # 2021-01-03 20 # 2021-01-04 25 # 2021-01-05 30 # Name: Temperature, dtype: int64 # # Index(['2021-01-01', '2021-01-02', '2021-01-03', '2021-01-04', '2021-01-05'], dtype='object') # [10 15 20 25 30] # Temperature # int64 # (5,) # 1 # 5

Here, we used a list to create a Series and specified the row and column names. Simultaneously, we output some basic information about the Series.

We can also use dictionaries and arrays to create Series:

python

# Create a Series using an array

import numpy as np

data = np.random.rand(5) * 10

ser = pd.Series(data)

print(ser, '\n')

# Create a Series using a dictionary

precipitation = {'2019-01-01': 0.5, '2019-01-02': 0.6, '2019-01-03': 0.7}

ser = pd.Series(precipitation)

print(ser)

# Output:

# 0 8.206034

# 1 4.538582

# 2 2.943366

# 3 5.961249

# 4 1.947226

# dtype: float64

#

# 2019-01-01 0.5

# 2019-01-02 0.6

# 2019-01-03 0.7

# dtype: float64

As seen, when creating a Series with an array without specifying an index, the default index starts from 0. If we want to specify the index, besides passing the index parameter to the Series() function during creation, we can also assign a value to the Series’s index attribute. The same applies to the name parameter and the Series values.

When using a dictionary for creation, since key-value pairs inherently have a correspondence, the dictionary’s keys automatically become the index.

python

data = np.random.rand(5) * 10 ser = pd.Series(data) print(ser, '\n') ser.name = 'Random Data' # Assign/modify the Series's name attribute ser.index = ['A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E'] # Assign/modify the Series's index attribute ser['A'] = 100 print(ser) # Output: # 0 8.465683 # 1 9.895826 # 2 7.659089 # 3 7.852485 # 4 0.819119 # dtype: float64 # # A 100.000000 # B 9.895826 # C 7.659089 # D 7.852485 # E 0.819119 # Name: Random Data, dtype: float64

DataFrame

DataFrame is the most important data structure in Pandas, used for storing and processing tabular data. A DataFrame can be understood as an ordered collection of two-dimensional data of equal length, where each column can have a different type (numerical, string, boolean, etc.).

Using DataFrames to simplify data processing steps can greatly liberate us from the tedious work of spreadsheet calculations in Excel.

The creation of DataFrames is also diverse. Let’s look at some simple examples:

python

# Create a DataFrame using lists temperature = [20, 21, 19, 22, 20, 21, 20] humidity = [60, 65, 55, 70, 60, 65, 60] precipitation = [0.5, 0.6, 0.4, 0.7, 0.5, 0.6, 0.5] df = pd.DataFrame([temperature, humidity, precipitation], index=['temperature', 'humidity', 'precipitation']) print(df, '\n') df = df.T # Transpose print(df) # Output: # 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 # temperature 20.0 21.0 19.0 22.0 20.0 21.0 20.0 # humidity 60.0 65.0 55.0 70.0 60.0 65.0 60.0 # precipitation 0.5 0.6 0.4 0.7 0.5 0.6 0.5 # # temperature humidity precipitation # 0 20.0 60.0 0.5 # 1 21.0 65.0 0.6 # 2 19.0 55.0 0.4 # 3 22.0 70.0 0.7 # 4 20.0 60.0 0.5 # 5 21.0 65.0 0.6 # 6 20.0 60.0 0.5

Here, we assumed temperature, humidity, and precipitation for a region and combined these three-element lists into one DataFrame. Since lists are arranged by row by default, we transposed the DataFrame using .T (In practice, once we understand Pandas’ indexing methods later, we can add data by column without needing such an operation).

python

# Create DataFrame from an array

data = np.random.rand(5, 3) * 100

df = pd.DataFrame(data, columns=['A', 'B', 'C'])

print(df, '\n')

# Create DataFrame from a dictionary

data = {'temperature': [22, 23, 21, 20, 19], 'humidity': [60, 65, 70, 75, 80], 'pressure': [1013, 1015, 1018, 1020, 1022]}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print(df)

# Output:

# A B C

# 0 50.327108 2.472678 77.686190

# 1 57.443441 79.428833 40.798433

# 2 7.028998 32.522689 73.435392

# 3 97.450968 17.192801 62.600331

# 4 14.854463 63.912453 90.014157

#

# temperature humidity pressure

# 0 22 60 1013

# 1 23 65 1015

# 2 21 70 1018

# 3 20 75 1020

# 4 19 80 1022

Arrays and dictionaries can also create Pandas DataFrames. For arrays, their arrangement aligns with the DataFrame; for dictionaries, the keys are read as column names (In a DataFrame, differences in column names essentially represent the fundamental distinctions between data, while row names are just labels for specific content within the same column), and the values are read as data.

When creating a DataFrame from an array, we specified column names via the columns parameter. This is a difference from Series; since a Series has only one column, it uses the name parameter to denote the single column name.

Similarly, we can modify or assign values to parameters like columns through assignment.

python

data = {'longitude': [10.0, 20.0, 30.0],

'latitude': [40.0, 50.0, 60.0],

'elevation': [70.0, 80.0, 90.0],

'temperature': [100.0, 110.0, 120.0],

'humidity': [130.0, 140.0, 150.0],

'pressure': [160.0, 170.0, 180.0]

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print(df, '\n')

df.index = ['A', 'B', 'C']

df.columns = ['Longitude', 'Latitude', 'Elevation', 'Temperature', 'Humidity', 'Pressure']

print(df, '\n')

# Output:

# longitude latitude elevation temperature humidity pressure

# 0 10.0 40.0 70.0 100.0 130.0 160.0

# 1 20.0 50.0 80.0 110.0 140.0 170.0

# 2 30.0 60.0 90.0 120.0 150.0 180.0

#

# Longitude Latitude Elevation Temperature Humidity Pressure

# A 10.0 40.0 70.0 100.0 130.0 160.0

# B 20.0 50.0 80.0 110.0 140.0 170.0

# C 30.0 60.0 90.0 120.0 150.0 180.0

Pandas Data Indexing

After learning NumPy’s indexing mechanism, Pandas’ indexing is straightforward. However, due to the existence of row and column names, Pandas’ indexing mechanism is more flexible than arrays.

Pandas indexing can be divided into two categories:

- Label-based indexing: Index data using labels (row/column names).

- Position-based indexing: Index data using positions (row/column locations).

Below, we’ll illustrate its basic usage directly through examples:

python

data = {'longitude': [10.0, 20.0, 30.0],

'latitude': [40.0, 50.0, 60.0],

'elevation': [70.0, 80.0, 90.0],

'temperature': [100.0, 110.0, 120.0],

'humidity': [130.0, 140.0, 150.0],

'pressure': [160.0, 170.0, 180.0]

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print(df, '\n')

# Using label-based indexing

print(df['longitude'], '\n') # Using brackets to index a single column

print(df.loc[:, 'latitude'], '\n') # Using loc to index specific row/column labels

print(df.loc[1, ['temperature', 'pressure']], '\n') # Index specific row/column labels

print(df.loc[:2, 'humidity':], '\n') # Label-based range indexing is inclusive (closed interval)

# Using position-based indexing

print(df.iloc[0, 0], '\n') # Using iloc to index specific row/column positions

print(df.iloc[1:, 1:3], '\n') # Position-based range indexing is left-inclusive, right-exclusive (same as array indexing)

print(df.iloc[:2, 2:-1:2], '\n')

# Output:

# longitude latitude elevation temperature humidity pressure

# 0 10.0 40.0 70.0 100.0 130.0 160.0

# 1 20.0 50.0 80.0 110.0 140.0 170.0

# 2 30.0 60.0 90.0 120.0 150.0 180.0

#

# 0 10.0

# 1 20.0

# 2 30.0

# Name: longitude, dtype: float64

#

# 0 40.0

# 1 50.0

# 2 60.0

# Name: latitude, dtype: float64

#

# temperature 110.0

# pressure 170.0

# Name: 1, dtype: float64

#

# humidity pressure

# 0 130.0 160.0

# 1 140.0 170.0

# 2 150.0 180.0

#

# 10.0

#

# latitude elevation

# 1 50.0 80.0

# 2 60.0 90.0

#

# elevation humidity

# 0 70.0 130.0

# 1 80.0 140.0

The above covers basic DataFrame indexing operations; Series is similar.

python

ser = pd.Series([10.5, 20.7, -5, 3.14, 7.89], index=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'], name='Temperature') print(ser, '\n') print(ser['a'], '\n') # Since there's only one column, bracket indexing defaults to row labels print(ser[['a', 'b', 'c']], '\n') print(ser.loc['b'], '\n') print(ser.loc['d':], '\n') print(ser.iloc[:-1:2], '\n') # Output: # a 10.50 # b 20.70 # c -5.00 # d 3.14 # e 7.89 # Name: Temperature, dtype: float64 # # 10.5 # # a 10.5 # b 20.7 # c -5.0 # Name: Temperature, dtype: float64 # # 20.7 # # d 3.14 # e 7.89 # Name: Temperature, dtype: float64 # # a 10.5 # c -5.0 # Name: Temperature, dtype: float64

Thus, we can use the indexing mechanism to flexibly assign and modify data.

python

df = pd.DataFrame() df['temperature'] = [20, 21, 19, 22, 20, 21, 20] df['humidity'] = [60, 65, 55, 70, 60, 65, 60] df['wind_speed'] = [10, 15, 5, 20, 10, 15, 10] df['rainfall'] = [0, .1, 0, 2, 0, .5, 0] df['weather'] = 'Sunny' df.index = ['2020-01-01', '2020-01-02', '2020-01-03', '2020-01-04', '2020-01-05', '2020-01-06', '2020-01-07'] print(df, '\n') df.loc['2020-01-01', 'temperature'] += 273.15 df.loc['2020-01-02', 'rainfall'] *= 1000 df.iloc[3, 1] = 1e4 df.loc['2020-01-04', 'weather'] = 'Rainy' print(df) # Output: # temperature humidity wind_speed rainfall weather # 2020-01-01 20 60 10 0.0 Sunny # 2020-01-02 21 65 15 0.1 Sunny # 2020-01-03 19 55 5 0.0 Sunny # 2020-01-04 22 70 20 2.0 Sunny # 2020-01-05 20 60 10 0.0 Sunny # 2020-01-06 21 65 15 0.5 Sunny # 2020-01-07 20 60 10 0.0 Sunny # # temperature humidity wind_speed rainfall weather # 2020-01-01 293.15 60 10 0.0 Sunny # 2020-01-02 21.00 65 15 100.0 Sunny # 2020-01-03 19.00 55 5 0.0 Sunny # 2020-01-04 22.00 10000 20 2.0 Rainy # 2020-01-05 20.00 60 10 0.0 Sunny # 2020-01-06 21.00 65 15 0.5 Sunny # 2020-01-07 20.00 60 10 0.0 Sunny

Postscript

After completing the study of NumPy and basic Python syntax, our subsequent content will have more practical value. This introduction to Pandas will lay the foundation for our deeper exploration of Pandas in handling various types of tables.